Dress For Success: Business Attire in Italy

Posted on December 12th, 2013 by Anna in Uncategorized | No Comments »

Dressing for a formal occasion in Italy, whether it’s a dinner, a corporate meeting, or any other important occasion, can be quite intimidating. Italy is the country of Prada, Gucci, and Armani, and first impressions are crucial in the developing of business relationships; dressing with elegance and panache can mean the difference between respect and derision, success and failure. So no pressure.

First of all, for both men and women, it is expected that you wear name brand labels, professionally tailored suits of either wool or silk, and expensive shoes. For men, stick to dark colors; black and navy blue suits are the safest, but a dark grey suit is also appropriate for business situations. Your tie must be both professional and fashionable; when it comes to patterns, paisley and stripes are both appropriate. Men can have a little more freedom with their shirts—bright colors are allowed as long as it matches both your tie and your business suit. Always wear a long-sleeved shirt, even in the summertime, and by no accounts should you ever be seen wearing shorts, which will mark you out as a tourist. Stay away from accessories of any sort, aside from an expensive, high-quality watch and leather belt to accentuate your professional attire.

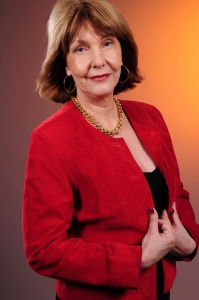

Women are also expected to wear dark-colored business suits with a blouse underneath to a professional meeting or gathering. When in the office, a dress or skirt is acceptable as long as it exudes a professional demeanor—obviously, no backless dresses or miniskirts, no matter how high-end the designer. Italian women, even in the workplace, tend to wear more makeup and jewelry than women of other nationalities, but make sure that it’s tasteful and ties your outfit together.

As for other aspects of dress, there are plenty of details that can also greatly influence the impression you give of yourself; for men, always make sure you wear knee-high socks rolled up, as it is considered unseemly to have any part of your leg showing underneath your trouser cuff. Shoes are just as important as the rest of your wardrobe, so make sure that your shoes are of high quality and without scuffs or blemishes. Men should wear leather shoes with pointed or square toes, and women should wear high heels—two inches is standard in corporate situations, but you may see women in the office with three inches or more. It’s common for both men and women to wear good perfume or cologne, and for an extra good impression, buy an expensive leather briefcase and business card holder to prove how invested you are in giving off an air of organization and competence.

There are many finer rules to Italian business etiquette that can only be learned firsthand, by interaction with colleagues and gauging their reactions to various situations. In order to do that, it’s imperative that you travel to Italy with a decent understanding of the Italian language. Look into our Italian courses, or send us an enquiry to find out what program is right for you.