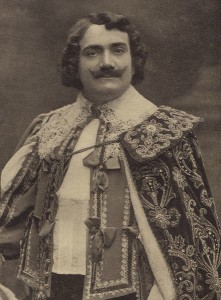

Enrico Caruso, Italy’s First Modern Superstar

Posted on November 8th, 2013 by Anna in Uncategorized | No Comments »

We tend to view the phenomenon of universally loved celebrities as something unique to the second half of the 20th century. After all, how cou

ld anyone even get famous without the help of television and the internet? However, the early 20th and even 19th century had th

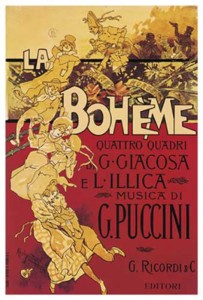

Born to a large, Roman Catholic family in 1873, Caruso grew up singing in the church choir, and later in the streets and cafes of Naples for money. After an inglorious beginning to his stage career, (he was received so poorly by Neapolitan audiences that he swore never to sing in his hometown again,) Caruso received a contract to sing at La Scala in Milan. He debuted in 1900, playing Rodolfo in Giacomo Puccini’s La Bohème. This was the beginning of Caruso’s shift from starving, unappreciated artist to international superstar. He went on tour to Monte Carlo, Warsaw, Buenos Aires, and even Russia, where he sang before the Tsar and his family in the Mariinsky Theatre of St. Petersburg. As a young and energetic upstart in the opera business, he was called on to take dynamic, romantic leading roles at La Scala, such as Maurizio in Francesco Cilea’s Adriana Lecouvreur and Cavaradossi in Puccini’s Tosca.eir celebrity idols as well—with fans just as adoring—thanks to the advent of new media and communication technologies, chiefly the telegraph and telephone. One of these turn-of-the-century luminaries was the opera tenor Enrico Caruso. Combining a powerful and versatile voice with a shrewd business sense and eagerness to take advantage of recording his performances on the gramophone, Caruso found himself launched to global fame, and to this day he is considered a paragon of Italy’s opera heritage.

In 1902, Caruso was called upon by the Gramophone & Typewriter Company to make a series of recordings, which immediately became bestsellers in both Italy and the English-speaking world, and Caruso signed on to sing in operas such as Don Giovanni and Rigoletto for London’s high-profile Convent Garden. After a year of performances in Italy, Portugal, and South America, Caruso went to New York City to premiere in Rigoletto at the Metropolitan Opera, where he continued to sing until the end of his life.

To aid his American career, Caruso signed on with the Victor Talking-Machine Company, and the series of discs he recorded spread like wildfire throughout American opera-lovers. For the first time ever, middle-class families were able to enjoy opera, through the radio and records, as well as the upper-class, making Caruso a musical hero with a truly widespread appeal—he was especially adored by half a million of New York’s immigrant community. He proved his patriotic fervor throughout World War I by giving concerts for charity and running Liberty Bond drives, and throughout the war years he invested all of his royalty earnings, leaving him a very wealthy man by the end.

Towards the end of his career, Caruso started taking on more dramatic, heroic roles, such as Don Jose in Carmen, Samson in Samson e Delilah, and Otelo. When Caruso died in 1921 of complications of bronchitis brought on by a heavy smoking habit and otherwise unhealthy lifestyle, his funeral in Italy was held at the Royal Basilica of the Church of San Francisco de Paola. He was there mourned by thousands of his admirers, including King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy. An idol to countless music-lovers, Caruso was one of the first artists to bridge the gap between opera as an old-century entertainment for the elite and an art-form to be enjoyed by all. He is honored in Naples to this day as one of Italy’s truly innovative musicians, an inspiration to all opera-singers after him.